Originally posted on Streets.mn.

Right now, and up until Monday, the Metropolitan Council is accepting public comment on whether or not to add the proposed Riverview Corridor streetcar project to its long range transportation plan. I encourage anyone who wants to see good transit service in Minneapolis-St. Paul to make it a priority to weigh in and express highly circumscribed support. The deadline to respond is Monday, January 21st, at 5:00 PM.

The Riverview Corridor is an important corridor for transit. It would directly connect downtown St. Paul to MSP International Airport and the Mall of America/South Loop, linking three large concentrations of housing, jobs, retail, and entertainment. The neighborhoods along the route are not as dense as they could be, but there’s room for growth and they are are laid out well for transit service. The existing #54 bus is not the system’s best performing route, but it is very popular, especially at peak hours. There is a reason why this corridor has taken so long to emerge atop the regional priority list, but its not wrong to believe that its time has come.

Unfortunately, Ramsey County and St. Paul’s recent political leadership have made choices for the corridor that have delayed investments in better transit. The corridor was once anticipated to be the second aBRT route, labeled the B-Line. However, local officials convinced Metro Transit to allocate their money elsewhere, with the justification that investing in better transit along the corridor today might preclude even better transit along the corridor tomorrow. I believe that opposite is true; the success of aBRT service on the Riverview Corridor would’ve strengthened the case (both locally and also in winning competitive federal grants) for further upgrades in service, including rail. The costs for this myopia are being borne entirely by transit riders in the corridor. In passing up the opportunity for aBRT service that would, at this moment, be operational, political leaders have forced current and potential riders along the corridor to wait over a decade before they see improvements.

The aBRT deferment has been compounded by a greater mistake, against which I urge readers to submit their comments. After a multi-year pre-project study led by Ramsey County (Disclosure: the study’s consultant firm is also my employer—I have not discussed the project with anyone within the company, and am unaware of anyone who was on the project team), the study’s steering committee chose a modern streetcar option as the locally preferred alternative. This mode choice would cost exponentially more than aBRT service ever would have, take far more time to build, and provide slower end-to-end travel times. It would also cost a similar amount to light rail service, take a similar amount of time to build, and also provide slower and less reliable end-to-end travel times with far less capacity. The result of the study is an alternative that will not improve transit in the corridor, while still costing an enormous amounts of money and time.

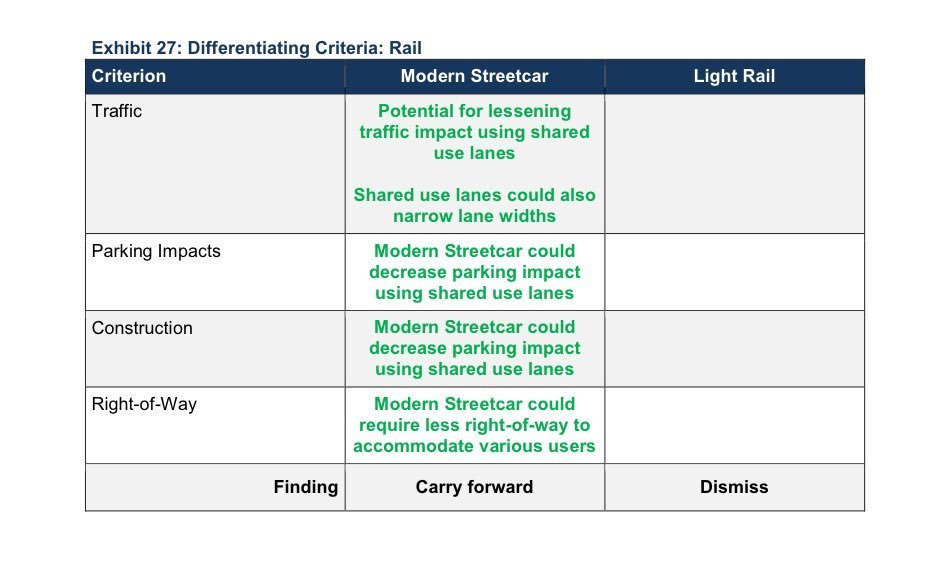

A chart from the pre-project study.

As I wrote at the time, this mode choice was made for all of the wrong reasons. In formally comparing the streetcar and light rail alternatives and dismissing the latter, the study examines the issue exclusively from the perspective of a driver or local property owner (see the chart above, which was taken from the pre-project study summary document). This entirely omits the significant differences between the two modes as experienced by their actual users. Ostensibly, this transit investment is being made for the benefit of the people who would use it. But how can that be the case, when the most critical decisions on the project are made based exclusively on their impact to drivers? When decision makers are not transit riders themselves, the inevitable consequence is that the interests of riders are sacrificed to appease more immediate constituencies. That is what has occurred here. There must be better ways to accommodate the needs of these other groups without sacrificing the utility of the project itself.

Interested parties should expect and demand better when the project eventually advances to the Met Council, an agency that is staffed by people who really do use and care about transit, and that has largely done excellent work to date. While the agency seems highly likely to add the Riverview Corridor to its 2040 transportation plan as requested, it should do so with a mandate to revisit the flawed assumptions that guided the pre-project study, and without formally committing to the streetcar mode choice. There are three signal flaws of the pre-project study’s recommendation, which are each compelling reasons for the Met Council to proceed in this way.

1. Dedicated Right-of-Way Is Essential To The Success Of Rail Transit

The primary difference between “light rail” and “streetcar” modes is that the former operates on its own exclusive track, while the latter shares space with ordinary passenger vehicles. When transit has its own right-of-way, it can move quickly and predictably, because nothing is ever in its way. This provides it with a critical advantage over other modes of transportation. When transit (especially rail transit, which cannot steer around obstructions like a bus) is forced to share space with other less efficient modes, like private cars, it forfeits this tremendous advantage and often moves more slowly and at a less predictable rate.

A streetcar in Tucson, AZ. In this case, it’s the streetcar blocking other vehicles. Photo by the author.

This matters to riders. The Canadian city of Toronto, which has continually operated its prewar transit system, recently attempted a pilot project that changed traffic patterns on a major street to get cars out of the way of the streetcars. The reliability and speed of the service improved, and ridership jumped 30% almost immediately. In contrast, across the United States, cities that have built modern streetcar projects in mixed traffic have been disappointed by the ridership. The most successful modern streetcar services in operation today are free, and when fares have been implemented, the results for ridership have been catastrophic. To a large number of users, the quality of service provided by these streetcars is not worth paying for. In proposing a streetcar service with up to six and a half miles of new track, St. Paul would dramatically upscale a model for transit that has failed to meet expectations across the country.

It is true that the plans for the Riverview project mollify this concern slightly because they call for the streetcar to run in dedicated right-of-way for much of that route (the exact alignment remains to be determined). While this is better than nothing, it is less important than it seems in this case. Any points of conflict with other vehicles are potential areas of trouble (as Green Line riders have occasionally discovered when there is an issue at intersections), and the portion of the route intended for mixed traffic is the portion closest to downtown St. Paul, which is the most congested area in the entire corridor. It is precisely when conditions are the most limiting for mobility that dedicated right-of-way transit has the greatest advantage, and where transit in mixed traffic suffers the most. The most successful streetcar system in the US, located in Philadelphia, runs inconsistently in mixed traffic in residential neighborhoods. But it remains a successful system because it enters a subway underneath two major universities and the downtown, avoiding the heaviest areas of traffic congestion.

This principle applies to mobility-limiting conditions beyond rush hour, which a personal experience can illustrate. On the first of December last year, my girlfriend and I went to lunch at the wonderful new Keg and Case Market on West 7th. We planned afterwards to drive with a friend into downtown St. Paul to get drinks at Barrel Theory Brewing, then to hop on the light rail to Minneapolis to see the Timberwolves play the Celtics. But an afternoon and evening snowstorm complicated our plans. In normal conditions, it would’ve taken us just ten minutes to drive between the food hall and the brewery. But in the wintery conditions, cars were traveling single-file down West 7th, the bridge over the railroad tracks at Grace Street was especially treacherous, and the trip took nearly forty-five minutes. A streetcar along this route would have been caught in the same traffic. In contrast, the trip on the Green Line from the Union Depot Station to the Warehouse District Station took more or less exactly as much time as had been anticipated. With dedicated right-of-way, our light rail train had no issues keeping to its schedule despite the snow and ice.

The experience of cities across the United States and Canada has demonstrated that operating in mixed traffic can slow down streetcars even in the best of conditions. It may still be true that the expected difference in travel time between a Riverview light rail service and a Riverview streetcar is not significant for many trips, because the weather is often fine and traffic is only occasionally congested in downtown St. Paul. It may also be true that other improvements, like traffic signal priority, might help move the streetcar along. But there will be times and dates, especially at rush hour and in winter, where the advantage of dedicated right-of-way of light rail would make a significant difference between the quality of transit service, and it is at these moments when the need and demand for that service is greatest.

2. Dedicated Right-of-Way Is Important To The Success Of The Entire METRO System

The DC streetcar connects to nothing, it is a transit orphan. Photo by the author.

One of the primary advantages of the proposed Riverview route will be that it will interline with the existing light rail routes on either end. In downtown St. Paul, it is planned to merge with the existing Green Line tracks, and serve Central and Union Depot Stations. Near the airport, it will merge with the Blue Line tracks and serve all stations west of Fort Snelling. These shared sections will give riders the ability to transfer easily between routes.

But the benefits to riders would be lost if the interlining causes delays throughout the METRO rail system. Currently, the Blue and Green Lines occasionally experience delays when merging track in downtown Minneapolis, as trains from each line are running too close in time to each other. Ultimately one train must wait while the other goes. If you are a regular user of the light rail, you have experienced this frustrating delay, looking up at US Bank Stadium and wondering when your train will move, or whether the Vikings will ever make an important field goal.

These problems will occur naturally as a result of the interlining planned for the Riverview route. But the problems could be far greater because of the problems inherent to the lack of completely dedicated right-of-way for the streetcar. The delays entering downtown Minneapolis occur despite the highly planned schedules of each train and each route’s mostly obstruction-free path. But because it runs partially in mixed traffic, the Riverview streetcar will run off schedule as a matter of course. These unpredictable delays will subsequently cause problems when the streetcar must merge and share track with the existing light rail service. In turn, these delays might then impact the timing throughout the system, including entering downtown Minneapolis, leading to repeated frustrating waits for riders, and a lot of hair-pulling for Metro Transit schedulers and operators. In this way, the choice to not run Riverview transit in an exclusive right-of-way hurts not just its own future riders, but also future riders of all METRO trains.

3. Single Car Trains With Smaller Stations At Smaller Intervals Will Hamstring The Route From The Start

While sharing right-of-way with other vehicles is the calling card of a modern streetcar, there are other disadvantages that almost always come along with modern streetcar projects (although there is no inherent reason why they should). A common example is that modern streetcar services in the US all use single car trains, tend to build smaller platforms that can only accommodate that one vehicle, and tend to place stations more closely together than is common with other urban rail. While not directly decided upon in the pre-project study, I fear the Riverview project will inexorably roll into the same choices. All three do a disservice to riders.

A streetcar in Portland, OR. Photo by the author. Small stations are easier to install, but less useful in the long run. Photo by the author.

Smaller trains and smaller stations mean less capacity, eliminating one of the key distinguishing factors between bus and rail. There is a fundamental paradox at the heart of this project, that will ultimately run into a buzzsaw at the federal grant level if not resolved. Does (or will) the Riverview Corridor have the ridership that merits a massive transit investment? If yes, than it requires at least two car trains, with stations that can serve three, like the existing Blue and Green Lines. If not, then there is no reason to spend two billion dollars on a corridor whose transit needs could be easily met by a better bus. The current proposal seems to imply that it’s possible to have it both ways; a billion in federal money, but not enough ridership to support running more than a single S70.

In truth, the Riverview Corridor is a marginal one, from a local and national perspective. The projected capital cost per weekday rider is already in the “medium-low” priority category for the federal funding formulas. The strongest case for such an expensive transit investment in the Riverview Corridor would be if the surrounding neighborhoods got significantly denser in a hurry. But more density would also necessitate more capacity and better service. The better the case for transit in the corridor, the less well a streetcar would serve it.

Smaller trains and smaller stations also mean that the Riverview transit would be badly suited for handling major events in downtown St. Paul, especially professional men’s hockey games. One minor success of the Twin Cities’ light rail system has been its enthusiastic embrace by professional sports fans, who pack onto trains before and after games. Many fans from the south and western metro often drive to park and ride lots along the end of the Blue Line, and take the train to games in downtown Minneapolis. Undoubtedly many fans would like to have the same option to reach Wild games, but the capacity of the streetcar would not sufficiently support this use. The needs of this group are relatively minor when compared with regular weekday riders, but it is genuinely striking that such an obvious and easy use of the train would be precluded from the start.

From smaller trains and smaller stations apparently flows the thinking of smaller distances between stations. Outside of downtowns and the someday-maybe future downtown in the South Loop, both existing and planned light rail routes have stops no less than half a mile apart. But the Riverview pre-project study call for at least three pairs of stations that are unnecessarily close, and would slow down the trains without providing much in the way of new riders. There are stops planned for both Davern and Maynard Streets, which are just 1,000 feet apart. There are stops planned for Homer and Montreal Streets, which are just 2,000 feet apart, and in the least populated area of the corridor. In downtown St. Paul, there is a split stop planned in the vicinity of Wabasha Street, of which the closer portion could lie less than 700 feet from the existing Central Station. Hopefully these redundant stops will be eliminated as the project is further refined. But given that the study at times highlighted smaller stop spacing as an intrinsic feature of the streetcar mode, I worry that the project will ultimately be developed with more stations than needed, further delaying travel times and wasting money.

Where The Process Goes From Here

The deadline for public comment on the Riverview Modern Streetcar proposal is Monday, January 21st, at 5:00 PM. If you are interested in submitting a comment, you must do so before then. After the conclusion of the comment period, the Met Council will vote on adding the project to the “Current Revenue Scenario” of their 2040 Transportation Policy Plan. This means the Met Council expects to start working on the project in the near-ish future. It’s a big step.

It also means that there’s a long way to go, and no time to waste. The FTA has a formal process for transit projects looking for federal grant funding. This process has two main stages; Project Development, which is expected to take two years, and Engineering, which is a bit more open-ended, but requires that significant progress be shown within three years. Construction and testing might take four years, totaling a nine-year process if everything goes smoothly. For revenue service to start in 2028, the Met Council might want to enter into the process fairly soon. While sometimes major project details can change fairly late on, it’s always better to be on the right track from the start. Planners with Ramsey County and the Met Council need to hear from transit riders and advocates that the interests of the line’s users must be the first consideration in designing an extension of the METRO system, and that the proposed modern streetcar does not meet that criteria.

A feature and a bug of the way that transit is built in this country is that it happens in giant leaps and bounds, instead of incrementally. That means that when you build, it’s critical to get things right the first time. That can still happen here, but if transit users and advocates speak out, I believe something better will come out of the process.