Originally posted on Streets.MN.

By one count, there are over 7,600 streets named “Main Street” in the United States. But there is only one that became the title of Nobel Prize winner Sinclair Lewis’ 1920 classic “Main Street”, and that’s the one in Sauk Centre, MN (alias “Gopher Prairie”), the writer’s hometown.

Main Street—the novel—is about a progressive and urbane woman from St. Paul, who moves with her husband to Gopher Prairie and becomes frustrated with the provincialism and lack of initiative of small-town life.

Main Street—the street—has three lanes, two parking lanes, and sidewalks. It is lined with stores and carries 10,700 vehicles per day at its intersection with Sinclair Lewis Avenue (!) at the center of town. In an ironic reversal from its literary role, it has also become ground zero for a forward-thinking initiative that has the potential to not just change life in Sauk Centre, but also on Main Streets across the state. Its only obstacle may be provincialism and lack of initiative in St. Paul.

In this modern-day retelling, the story would instead be titled “Minnesota Trunk Highway 71”, and the roles of both the sophisticates and the yokels would be played by different groups within the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT). The story would begin this summer, when MnDOT put in place a protected bike lane and some curb extensions on that literary street. Where the story goes from there depends on whether this demonstration becomes a footnote for the department’s engineers, or a foothold for a new way of doing the business of a DOT.

Safe Streets In Small Towns

The project in Sauk Centre is one of eight around the state that are being implemented by a group within the department focused on promoting walking. Like most of its peer departments around the country, MnDOT was once known as a ‘Department of Highways.’ Thinking about walking is an unfamiliar role for these agencies.

But walking is transportation, and whether it has always been aware of it, MnDOT’s choices on almost every project have had an impact on the ability of people to walk around.

With great frequency, that impact has been negative. In some cases, pedestrians are not accommodated at all in major transportation projects. When they have been, that accommodation has often been formulaic, with little thought given to critical issues for pedestrians like comfort or convenience. Even considerations of pedestrian safety, which theoretically should be in the wheelhouse of highway engineers, have all-too-often been compromised in favor of the agency’s longstanding primary goal of moving more cars more quickly.

Yet this harmful practice might be changing. The reconstruction of picturesque Trunk Highway 61 in Lake City offers some promising evidence. As it previously existed, this road (also known as Lakeshore Drive) carried four lanes of fast traffic straight through the city’s retail district. The people of Lake City decided that this didn’t suit their needs, and through their comprehensive plan, called for traffic calming. To its credit, MnDOT listened, and moved forward with a project that included a 4-3 lane conversion, medians, and larger bump-outs. The work was finished this summer.

A rendering from the MnDOT project in Biwabik. Image: MnDOT

An even more involved project is underway in the Iron Range town of Biwabik, which is built around Trunk Highway 135. This small-town strip (also known as Main Street) has two lanes of traffic and two little-used parking lanes that make the road seem far wider, with shops, restaurants, bars, and civic buildings on both sides. It’s a thoughtless design, and MnDOT’s reconstruction project is implementing a far more thoughtful approach. The new Main Street will feature landscaped medians at both ends of the town, widened crosswalks, and bump-outs. Construction will be complete next year.

The root of MnDOT’s more-promising recent work is the agency’s Complete Streets policy, which germinated from a direction passed by the state legislature in 2010. This policy calls for the needs of all road users to be considered and documented as a part of every project. But noticing these needs and acting on them—actually fulfilling them— are two different things. Pedestrians and bicyclists, more than drivers, are especially sensitive to issues of comfort, convenience, and safety. The details matter. It’s entirely possible to “consider” them in a way that is not much better than no consideration at all.

Think Global, Act Local

Taken project by project, these issues seem small. But collectively they matter more than the sum of their parts. Minnesota’s state highway system carries 57.5% of all vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in the state. It reaches just about every town and city, often passing straight through their cores (as in Sauk Centre). The right-of-way controlled by MnDOT is of central importance to just about every community and the state as a whole.

It’s also of critical importance to Minnesota’s efforts to mitigate climate change. Transportation is the state’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, and the volume of these emissions is closely correlated with the amount of VMT. These facilities are entirely within the control of MnDOT and whether emissions and VMT go up or down is a conscious choice that the agency’s leadership and staff make.

Unfortunately, the agency has not always been willing to admit this. Last year, MnDOT released a report entitled Pathways to Decarbonizing Transportation. It was an interesting report with a lot of interesting modeling. But it also placed significant focus on exploring emissions reductions strategies that the agency has little control over (the rate of adoption for electric cars), and downplayed strategies that are completely within its power (like reducing VMT). This is why I wrote in response to the report, that “MnDOT needs to challenge itself to reduce VMT.”

The same point was made in a 2020 report called Driving Down Emissions in Minnesota that was produced by a partnership between national groups Smart Growth America and Transportation For America and state sponsors Move Minnesota. The report notes that “[the Pathways report] suggests that emissions targets can be achieved with just a 5 percent or 10 percent VMT reduction in the Twin Cities metro area—and even allows for a VMT increase in the rest of the state… this approach will need to shift for Minnesota to achieve necessary reduction in emissions from the transportation sector.”

MnDOT is bound by law and common-sense to pursue policies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transportation. While the agency may resist some of the most disruptive changes, it could still pursue a popular and productive policy of both traffic calming and pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure investments in the areas of small town and cities that best support and demand it.

Think Local, Act Local

Taken project by project, these issues seem small. But locally they matter a great deal to towns and cities which might otherwise not see frequent state investment. Main streets have always been indicative of the health of their towns and cities. Ensuring that these streets are not just thoroughfares for people passing through, but places for locals to shop and gather, should be an important goal for Minnesota.

MnDOT can’t bring back every local business, but it can at the minimum ensure that the way it designs its roads helps and not hurts. In the past, the agency has helped erode the wealth of small towns and cities by either destroying it outright, or by undermining main streets with hostile design and subsidizing their competition.

Trunk Highway 10 conspicuously avoids cutting through the downtown of Perham, leaving it intact and thriving. Image: Google Maps

A short tour of some of Minnesota’s most successful small towns helps illustrate how local success and walkable main streets tend to be correlated. The Star Tribune recently reported on the northwestern town of Perham, which is defying the trend of rural population loss. It’s clear from the article that the town’s secret is rooted in local private corporations that have stayed local and continued to invest in the community. But I couldn’t help noticing that Perham has also benefitted because the local state highway bypasses the center of the town. While the lanes are still too wide and the sidewalks are still too narrow, it’s striking that bustling Perham’s Main Street carries just a single lane of traffic in each direction.

The southwestern town of Worthington has boomed in recent years in large part thanks to an influx of immigrants who work in the area’s pork processing industry. But here as well, the town has benefitted from proximity to the highway system (I-90 runs just north of town) without being gutted by it. Worthington’s multi-block core is made up of streets with just one lane of traffic in each direction, and the local state highway passes well clear to the south.

It is obviously not possible to claim that having a walkable downtown is the golden ticket to a town’s success, only that it can be a supporting factor. Just as denser, walkable patterns of housing and retail play a small role in helping reduce VMT and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, so do they also play a small role in making small towns and cities wealthier by raising the value of their land. MnDOT’s exclusive focus on automotive mobility has created sprawl throughout the state, not just in Twin Cities suburbs. If the agency began instead to focus on pedestrian comfort and convenience, it could start to have the reverse effect and ensure that the state is a constructive and not destructive partner in building local wealth.

Towards A Proactive Main Street Policy

MnDOT’s recent projects in unexpected places like Lake City and Biwabik suggest that the policy and practice of complete streets is embedding itself more deeply into the agency’s work. But there’s also room for improvement. The process is fundamentally reactive, intervening in highway projects that have already been initiated for other reasons. Yet the global and local issues at play are too pressing to be addressed as add-ons. It’s time for MnDOT to shift to a more proactive policy.

This summer’s demonstration projects in Sauk Centre and elsewhere show how that work might unfold. Unsafe or unfriendly roads in high-activity areas should be a reason in and of themselves to redesign and rebuilt a roadway. Designs can be piloted using cheap materials and paint, while funding and engineering for more permanent changes proceeds in the background. This is, of course, the same model that has been pioneered in cities across the world, but it’s one that’s still new ground for state DOTs.

The time to establish this kind of thinking and process in MnDOT is now. The agency is currently in the early stages of the process of updating Minnesota GO, the statewide transportation plan, and is currently accepting public input. At the same time, MnDOT recently is hearing from its all-star advisory groups about the critical need to plan for a reduction in VMT statewide. These types of efforts will help make a difference in the agency’s outlook.

But the single best opportunity to push MnDOT in the direction of safer, healthier, wealthier main streets comes in the form of the state’s draft pedestrian plan, which is open for comments until January 11th. This is one of a family of plans for different transportation modes, which all rest under the umbrella of Minnesota GO. These plans will have a significant behind-the-scenes impact.

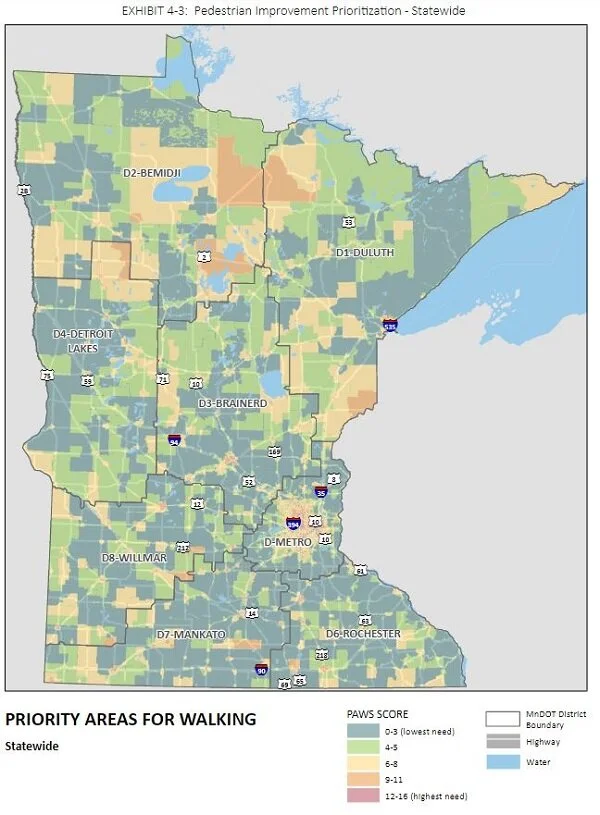

MnDOT’s draft pedestrian plan identifies priority areas for walking (PAWS). Image: MnDOT.

The draft pedestrian plan is extremely promising. It directly identifies the issue that "current MnDOT investments in walking are typically tied to projects that are primarily focused on car and truck traffic,” and that they “primarily focus [only] on meeting ADA standards.” It is clear-eyed that there are challenges for directly funding pedestrian-priority infrastructure, or for exceeding minimum standards for infrastructure when appropriate. To start building the case for more dedicated pedestrian money and projects, the plan presents a “Priority Areas for Walking Study” (PAWS) across the state. To fund improvements to state highways within the highest-priority priority areas, the plan estimates a total cost of $200-600 million, depending on the intensity of the changes.

I’d like to see MnDOT run with this plan. Some changes could be made immediately. For instance, the state’s Complete Streets Policy specifically exempts projects in wilderness, industrial parks, and several other contexts from having to document their complete streets considerations. But the policy should also work in the opposite direction, demanding special considerations in pedestrian-heavy areas, like retail corridors and areas with multi-family housing. These areas almost always correspond to the highest-priority PAWS areas. Projects should have to document how they gave pedestrians priority in these areas. Projects should have to require extraordinary documentation to justify travel lanes widths greater than 11’ and a cartway greater than 33’ in these areas. The PAWS framework gives the agency the justification it needs to enact directives like this.

Corridors Of (Local) Commerce

MnDOT should also take affirmative steps to imitate these projects for their own sake. In every single situation in which a state highway runs through a retail or multi-family residential area, the agency should reach out to the local municipality and begin a process for making near and long-term pedestrian and bicycle priority changes to the road.

It doesn’t take long to apply this method on Google Maps and identify promising candidates. For instance, Grand Rapids is gutted by an appalling five-lane design for Trunk Highway 2. There is clearly a local desire for a safer street, as shown by the raised and textured intersection at the center of town and bollards protecting the narrow sidewalks. But these interventions are inadequate to the task. This street carries, at most, 18,000 annual average daily traffic (AADT). The current layout is a deadly joke that deserves an urgent response.

Another illustrative case can be found back on Trunk Highway 2, where the state has creatively managed to ruin the downtown of Crookston. Despite an AADT of just under 13,000, the highway there has been split into parallel three-lane one-way racetracks that divide what would otherwise be a wonderful small downtown.

A final example is Alexandria’s utterly senseless five-lane main street, where, for the sake of an AADT just over 17,000, MnDOT has trashed an otherwise intact downtown. But here, at least, we can start to see what future progress might look like. While the large issues remain unresolved, this central Minnesota town was host to one of this past summer’s pedestrian demonstrations, which enhanced an existing median.

Fixing these streets demands a robust and aggressive infrastructure effort. I can’t help thinking that Minnesota has the perfect model in the Corridors of Commerce program. As it stands today, it functions as a sort of reverse complete streets policy, funneling money to the rare places in the state highway network that were not already supersized. But the effectiveness of the model can’t be disputed. With different criteria for funding, the same approach could be re-engineered to do the opposite, directing hundreds of millions of dollars into quick-turnaround projects that would rebuild complete streets in the most critical areas (like those called out in the PAWS analysis).

If Minnesota and MnDOT are serious about combatting climate change and supporting small businesses, they should recognize the opportunity that has been created by dedicated planners and engineers. What happened this summer on Minnesota’s most famous Main Street should set the stage for a transformation of main streets around the state.